The Triumphs and Tragedies of Dawn Powell, Central Ohio’s Forgotten Literary Genius

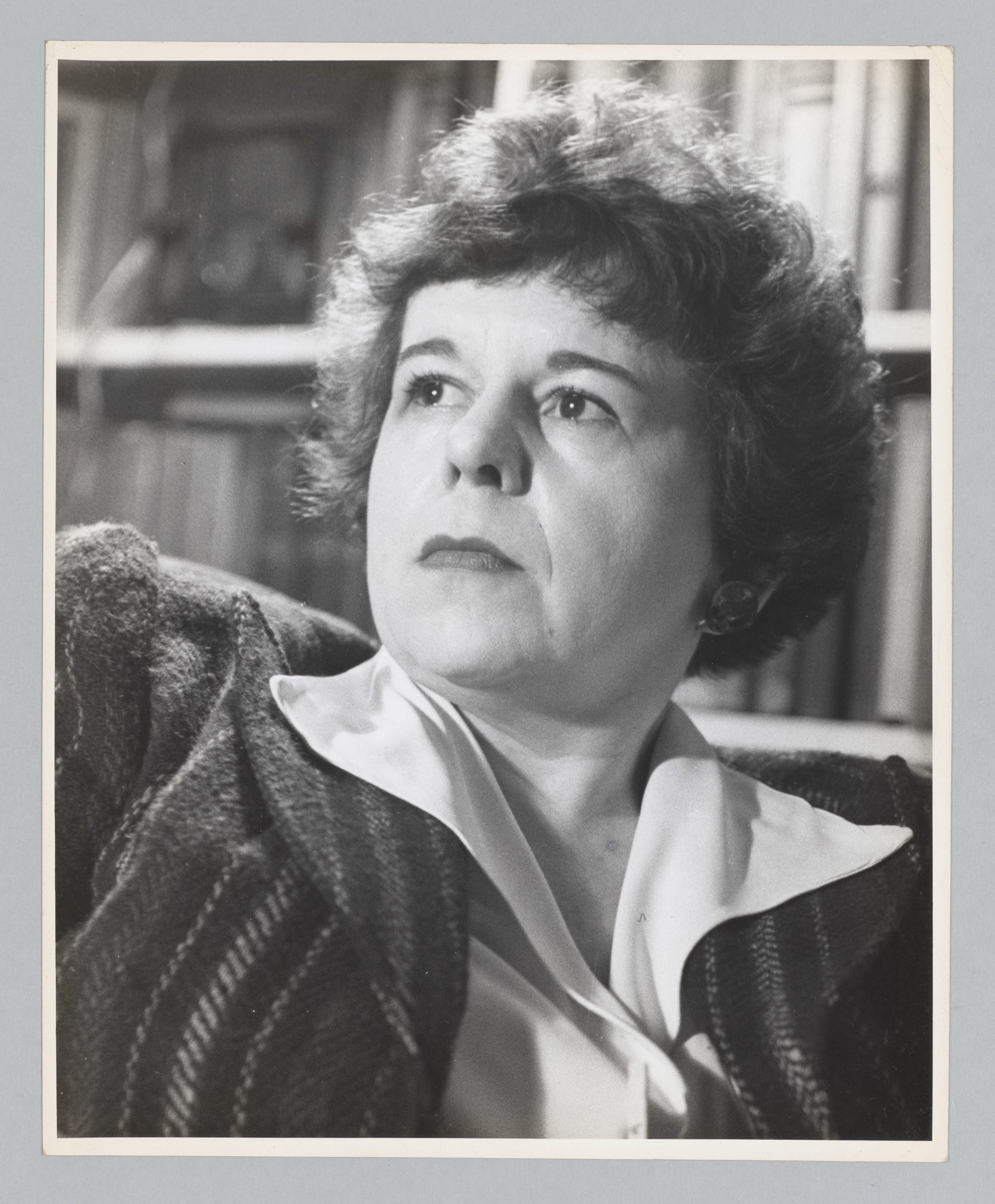

Though novelist Dawn Powell was a prolific writer and admired for her sarcastic and satirical musings, she was largely left out of literary history. Now, her most avid readers are clearing a space for her.

Once, long ago, radio airwaves were filled with wits and wags.

In 1939, several great American writers turned up on a short-lived radio game show called Author! Author! The conceit was simple: Ordinary listeners submitted “endings” to stories; the beginnings and middles were furnished by the writer panelists in a presumably entertaining fashion.

During one episode broadcast that year on the New York station WOR, humorist S.J. Perelman, drama critic John Chapman and writer Heywood Broun were joined by two Ohioans: writer and cartoonist James Thurber and novelist and playwright Dawn Powell. Thurber was already famous; Powell never would be. Perelman, who emcees the affair, good-naturedly joshes Powell about wearing the “famous Powell rubies at her throat.” Perelman asks: “Isn’t there some famous legend attached to those gems, Miss Powell?” Powell replies: “The only thing attached to them right now, Mr. Perelman, is a chattel mortgage put there by the Greenwich Savings Bank.” Ba-dum-bum.

It was one of the sad facts of Powell’s life that she often was the least well known in any company. “Dawn Powell … probably was very eager to get on national radio like that, and she’s very funny,” says New York writer Kevin Fitzpatrick, whose website on the Algonquin Round Table posted the long-lost broadcast after it was sent in by a collector.

The imbalance persists even in her home state. Decades after their deaths, Thurber has a house named after him in Columbus, also the site of a prominent literary center and museum; Powell has a lonely historical marker in her hometown of Mount Gilead, where she was born in 1896. The disparity is made worse because Powell’s artistic achievements may be just as significant as Thurber’s—or almost any other American writer’s.

Discover more forgotten history of Central Ohio:Subscribe to Columbus Monthly's weekly newsletter, Top Reads

During her lifetime, Powell was admired but not embraced. She was a prolific writer, producing plays, articles, book reviews, voluminous diary entries and, above all, more than a dozen ferociously tough-minded, largely comic novels. Some, such as “Dance Night” (1930) and “My Home Is Far Away” (1944), were empathetic but unsparing tales of the lonesome inhabitants of the state of her birth; others, the most well-known ones, including “Angels on Toast” (1940) and “A Time to Be Born” (1942), were satirical, sarcastic, sour send-ups of the movers, shakers and strivers in her adopted hometown of New York City.

A single novel, 1954’s “The Wicked Pavilion,” snuck onto The New York Times’ bestseller list. By then, however, Powell had endured her share of disappointments and tragedies—and after her 1965 death, she was the victim of persistent neglect. An inattentive literary executor did not help matters, but what really plagued Powell was the unsentimental astringency of her own writing. “Dawn’s work is incredibly lonely,” says New Yorker writer Rachel Syme. “The novels are sharp and bitter and acrid, and the diaries are angsty and often feel like the work of a very isolated person.”

More than two decades after Powell was buried in an unmarked mass grave on New York’s Hart Island, her friend Gore Vidal reintroduced her to the public in a 1987 New York Review of Books essay. He was Powell’s first posthumous champion, but he wasn’t the last. In the ensuing years, a host of celebrities, authors and critics have fallen for Powell. Her admirers include the likes of writer Fran Lebowitz, actress Anjelica Huston and Gilmore Girls showrunner Amy Sherman-Palladino, who namechecked Powell in a 2002 episode of the TV series. (“There are some who actually claim that it was Powell who made the jokes that Dorothy Parker got credit for,” aspiring writer Rory Gilmore said.) Earlier this year, Syme’s New Yorker colleague, film critic Richard Brody, became the latest media figure to celebrate Powell, declaring her nine novels written from 1929 to 1948 (including three about Ohio) “one of the most extraordinary outpourings of sustained literary artistry that the United States can boast.”

Indeed, when readers discover her work, Powell can have an intoxicating effect. WOSU radio host Christopher Purdy has been a Powell devotee since the early 1990s. “The first one I read was ‘A Time to Be Born,’” Purdy says. “I was immediately riveted by the bite of the prose. It was a little like Mozart, in that it sounded like it was written yesterday and not 70 years ago.”

Even among Powell’s famous fans, though, none has been more dedicated, persistent or zealous than Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Tim Page, who, after discovering Powell’s work by happenstance in 1991, embarked on a one-man effort to get her read again. Later, in rapid succession, Page assembled a hardcover selection of Powell’s work, 1994’s “Dawn Powell at Her Best”; edited editions of her extraordinary diaries and letters; and wrote an exemplary biography, 1998’s “Dawn Powell: A Biography.”

“It was as though a spell came over me,” Page says now.

Yet for all this recent love, the Powell revival has been fitful. “She’s had these waves of people getting interested in her,” Syme says. “She is everyone’s favorite discovery, and they tell everyone about it, but it’s not quite ever really caught on.”

In 2012, when Page was seeking to sell Powell’s actual diaries to a library or collector who would make them publicly available, the initial lack of interest was so striking that Syme’s New Yorker piece about the efforts bore this headline: “Dawn Powell’s Masterful Gossip: Why Won’t It Sell?” (Columbia University, to which Page had been giving Powell material all along, finally agreed to purchase the diaries.)

Even in her hometown of Mount Gilead, located about 40 miles north of Columbus, Powell is largely forgotten. When asked about local interest in Powell’s life and work, former Mount Gilead Public Library director Mark Kirk says that he didn’t see too much evidence of it during his time there. “I hate to say it,” says Kirk, who ran the library from 2006 to 2020 and is now the director of the Galion Public Library. “We always tried to keep her books in the library, just in case somebody was interested. … Dawn Powell’s been gone for 60 years, which shouldn’t have an effect, but it does.”

The situation isn’t much different in Columbus. Debra Boggs has spent 35 years working in independent bookstores in Central Ohio, including her current post as the store manager and book buyer at Gramercy Books in Bexley. Yet, in all that time—a time when, thanks to Page’s persistent interventions, Powell’s novels went from being in large measure out of print to being reissued in attractive paperbacks—Boggs says Powell’s name never came up. “I don’t remember anybody ever asking me about her, or asking for a book about her,” Boggs says.

It’s a disappointing final chapter in a life filled with them.

“Even though she lived in New York for 45 years,” Purdy says, “she never left Ohio, I don’t think.”

As a girl in Mount Gilead, Powell is known to have lived at two addresses: 53 W. North St., her family’s residence when she was born, and 115 Cherry St. Like her fellow Midwesterner Ray Bradbury, who was famous for saying that he recalled his own birth, Powell seems to have possessed something like total recall. “Within the family, her memory was renowned; she even claimed to remember being taken to the Bethel farmhouse as an infant,” Page writes in “Dawn Powell: A Biography,” referring to a farmhouse belonging to her mother’s family. “She was reading before she was 5; by the age of 9, she had made her way through the complete works of Alexandre Dumas.”

Yet—conforming to her future friend Edmund Wilson’s argument, in his classic book “The Wound and the Bow,” that great personal trauma can be a springboard for writers—Powell wouldn’t have had much to write about had her life not been torn asunder. She was 6 when she lost her mother (the talk was that she died following a botched abortion), and, in a different sort of way, she lost her father, Roy, who not only went out on the road but returned with a new wife, the hateful Sabra.

“Her stepmother was really a monster,” says Page, who, in his biography, recounts beatings doled out to Dawn and her sisters as well as a gruesome episode involving a premature child born to Sabra and Roy who died and, having been deemed by Sabra to have been buried in inappropriate attire, was exhumed, dressed again and buried a second time. Page says Powell left out of her autobiographical book “My Home is Far Away” the most horrible Sabra stories because she thought no one would believe them. At 13, when her family relocated to Northeast Ohio’s North Olmsted—a town, Page notes, that lacked a high school—Powell moved in with an aunt in Shelby, where Powell could receive an education.

Powell then enrolled at Lake Erie College for Women (today the co-educational Lake Erie College) in Painesville. There, Powell engaged in a torrent of creative activity. She played Puck in Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” She was one of the creators of a homemade, handwritten newspaper, The Sheet, and, more officially, she edited the Lake Erie Record. She graduated—“without honors,” Page writes, presumably due to her pursuits outside of the classroom—in 1918.

“In some ways,” says Adam Stier, an associate professor of English at the school, “it’s like Lake Erie provided a launching point into the rest of her life.”

Powell’s eastward trajectory remained fixed. After leaving Lake Erie College, she headed first to Connecticut, spending a summer on a farm with other artistic types, before landing in the place that would always tug at her emotions: New York City. In 1920, she married Joseph R. Gousha, who later became an advertising executive, and, the following year, she gave birth to their son, Joseph Jr., called “Jojo.”

Due to his unpredictable temperament, periodic outbursts and generally “off” behavior, Jojo was said to have had a variety of mental problems, receiving incorrect diagnoses of schizophrenia and cerebral palsy. “Now we would characterize him as autistic,” Page says.

While contending with Jojo’s challenges—as well as fault lines in her marriage that would never be fully resolved—Powell managed to cobble together a busy writing career. Setting up housekeeping in Greenwich Village, the destination for anyone with a bohemian bent, she seemed to thrive on bustle. Powell accepted workaday assignments, such as book reviews for the New York Post, while writing her novels, which, through the 1920s and much of the ’30s, drew explicitly on her Ohio roots.

After “Whither” (1925), her debut, came “She Walks in Beauty” (1928), “Dance Night,” “Come to Sorrento” (1932) and “The Story of a Country Boy” (1934). None were large critical or commercial successes, though they were well-regarded enough to draw interest from Hollywood, where Powell toiled unproductively (though not unprofitably—it was a rare instance in which she made real money from her writing). “The Story of a Country Boy” was made into a movie, as was Powell’s play “Walking Down Broadway.” “They’re both preposterous films,” Page says.

Powell’s Ohio novels have their partisans. One fan is WOSU book critic Kassie Rose, who, in 2005, featured Powell as part of a yearlong series of shows on Ohio authors. “She doesn’t romanticize the Ohio small-town life,” Rose says. “She also doesn’t make it seem bleak and suffocating like Sherwood Anderson.”

Starting with “Turn, Magic Wheel” (1936), though, Powell enlarged her canvas to include the smart set, the jet set and those striving to join either. By the time she published “A Time to Be Born”—her comic masterpiece centered on heroine Amanda Keeler, a fierce caricature of playwright (and spouse of publisher Henry Luce) Clare Boothe Luce—Powell was known, if she was known for anything at all, not as a regionalist but as a satirist of contemporary manners and mores.

“She was a completely different culture from us,” says her great-niece Vicki Johnson, a 72-year-old Massillon resident and the daughter of Carol Warstler, whose mother was Dawn’s younger sister, Phyllis. “She wined and dined with the Algonquin [Round Table]—she just hung out with those artists.”

Officially, Powell returned to the literary terrain of Ohio just once. She published her final Ohio novel, her best, “My Home Is Far Away,” two years after “A Time to Be Born.” But even when taking New York City as her subject, she remained, at heart, an Ohioan gone East. “I think she felt like an outsider in almost every scene that she was part of, even the literary world,” Syme says. “Her diaries are just constant lists of people who she feels like might not be her real friends, might not actually like her as much as they say they do.”

Even during her peak years, Powell’s life had a snake-bitten quality. In 1929, she began suffering from what she supposed was a heart condition but which was later revealed to be, ominously, a tumor known as a teratoma. Because this type of tumor can consist of hair and even teeth, the condition was misunderstood by Powell. “She had this idea that it was a failed twin,” Page says. “Apparently, that was a fairly common idea back then, and no one believes it anymore.”

Though they stuck out their marriage, Dawn and Joseph led independent lives. Alcohol use did not help. Then there was Jojo, who, his love for his mother notwithstanding, seems to have seriously injured her in an incident vaguely but dramatically alluded to in Powell’s diaries from 1947. Powell wrote then: “Stunned and frightened, Dos”—that’s John Dos Passos—“got me doctor, neurologist. Head no better. As if all forces, particularly treacherously loyal ones, were bent on keeping me from finishing book already at printer’s. Too battered to raise willpower yet but hope to.”

“He beat her pretty much within an inch of her life,” Page says of the incident with Jojo. “Dawn was in the hospital for a while. I still don’t know the exact things that happened, or what triggered it, and I guess nobody will ever know now.”

Given this environment, that Powell continued to write at all is miraculous, and it would be nice to say that all of her honest effort ultimately paid dividends. But there was no big break in the offing. “What is it like to get up in the morning and sit down on your fifth or sixth or seventh novel, and realize that all the ones before were underappreciated and undersold?” Kassie Rose asks, sensibly.

Following Joseph’s involuntary retirement in 1957, when he hit age 67, severe financial straits compelled Dawn and her husband to leave their apartment (which was, inconveniently, converted to a co-op around the same time); hotel rooms would suffice until prospects improved thanks to a rich friend. Joseph died in 1962. A final novel, “The Golden Spur,” was a succès d’estime.

In the end, it was not the loss of a parent or the reign of a horrid stepmother or the long journey from Mount Gilead to Greenwich Village or the frustration of literary neglect or even that strange tumor that finished off Dawn Powell: Colon cancer took her life on Nov. 14, 1965. She was 68.

“Dawn, like most people, did not think she was going to die until it became exceedingly obvious,” Page says. She had slapped together a will, ill-advisedly designating as her executor a young friend named Jacqueline Miller Rice. In a sign of things to come, Rice did not claim Powell’s remains when her body, left to science, was ready for burial; instead, Powell would spend eternity in that mass grave on Hart Island. Possibly even worse: Rice permitted several of Powell’s novels to fall out of copyright; overtures to make film adaptations went unanswered.

Christopher Purdy has some ideas about how to kick-start the great Dawn Powell renaissance, at least within Central Ohio. “I would love for there to be a two- to three-day symposium on her work, maybe at Ohio State or the Ohioana Library,” Purdy says. “You could also involve the [Ohio State] Theatre Department and do scenes from a couple of her plays. … You could do readings. Her work is not really pedantic or scholarly.”

Maybe the revival will take place even more modestly than that—with adventurous readers doing as they have done for years: reading one Powell novel, then another, then another. They tell their friends, who tell their friends, forming a daisy chain of Powell enthusiasts. This summer, Gramercy Books set up a table spotlighting Powell’s work. It’s a start.

Then again, maybe we need to think bigger. Page is blunt. “It will take a film,” he says, pointing to the renewed interest in the famously down-on-his-luck author Richard Yates: 16 years after Yates’ death, a movie adaptation of his great novel “Revolutionary Road,” with “Titanic” stars Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio, made his work a hot commodity.

But it’s not a new idea to bring Powell’s caustic, cutting vision to the screen. In the early 1990s, actress Anjelica Huston—the Academy Award-winning daughter of director-actor-writer John Huston—was given a copy of “Angels on Toast.”

“I thought it was delicious,” Huston says. “Then, after that, I read ‘A Time to Be Born,’ ‘Turn, Magic Wheel,’ all of the New York novels to begin with, and then the Ohio novels. … I just feasted on Dawn Powell for about a year.”

When you’re Anjelica Huston and you discover a new favorite writer, what do you do? You try to make a movie. Determined to direct “A Time to Be Born,” which she judged particularly cinematic, Huston first approached Carrie Fisher to write a screenplay. It could have been the perfect pairing: two wily, wise wits from different eras. But, when Huston went to meet with her, Fisher said she wanted to hand the project off to another writer. “So that kind of fell by the wayside,” Huston says.

Then there was the time when Huston, having written her own adaptation of “A Time to Be Born,” got the project in front of the manager of Julia Roberts; the actress was a fan of the novel. “[Roberts’ manager] took a meeting with me, in which she sat behind this big oak desk in an office in New York and threw a ball to her Weimaraner puppy and gave me a discourse on how a script for Julia should be written,” Huston says. “I left the office so disheartened I almost gave up on the project right there.”

As a last stab, Huston, soon to start shooting Wes Anderson’s “The Royal Tenenbaums,” decided she would slip a copy to her co-star, Gwyneth Paltrow. “I thought, ‘Well, you know, she’d be a good Clare Boothe Luce—Amanda Keeler,’” Huston says. “We did the movie. I never got a reply from her. It was an exercise in lovely young actresses not responding at all, on any level.”

Of course, that was more than 20 years ago. These days, readers and critics and even movie studio bosses are more attuned than they’ve ever been to the ways in which women writers’ voices have been silenced or overlooked. Maybe, finally, Powell will be given a fresh look.

“People are thinking about women writers a little bit more intensely and critically in the last decade, but especially since a lot of revelations have come out about the publishing industry and how male it is, and the canon is just completely white and male,” says The New Yorker’s Syme.

But if there are any hot young filmmakers out there contemplating the movie, television adaptation or streaming series that will launch the Powell renaissance, please check first with her biggest fan in Hollywood.

“If anyone dares to do it without me,” Anjelica Huston says, “they’ll have hell to pay.”

After eight months of reading Powell, reading about Powell and talking about Powell, I decide to visit the place from whence she came. On a pleasant day in early August, I take a day trip to Mount Gilead (pop. 3,700).

The Powell historical marker, the only visible acknowledgment of the greatest writer ever to emerge from Morrow County, is tucked beside the public library building. It’s obscured by library signage and slightly overgrown foliage. To passersby who take the time to read it, the marker offers the bare facts (and not much more) of Powell’s life.

Elsewhere, the village displays the emblems of modern, commercialized society. Yet, at least to my citified eyes, Mount Gilead appears more tethered to its past than similar places I’ve visited in rural Ohio. Maybe it’s the Victory Shaft Monument that stands at the center of Main Street—a solemn stone obelisk, built in 1919 in recognition of Morrow County’s enthusiastic war savings stamp efforts during World War I.

Apart from that historical marker, though, there’s not too much evidence that a great American writer passed through here. The Powell family’s house on West North Street was knocked down (another house sprang up in its place), but her subsequent residence on Cherry Street still exists. Looking at the modest, two-story green house with a generous front porch, I can almost imagine the girl who once inhabited those walls, soaking in the drama around her even as she longed to flee—to Shelby, to Painesville, to New York City.

The war dead may loom over Mount Gilead, but the village’s ghostliest presence is surely that of Dawn Powell.

This story is from the November 2021 issue of Columbus Monthly.