Serial Killer Michael Swango’s Unlikely Pen Pal

When Jennifer Harp-Yanka began corresponding with serial killer Michael Swango, she hoped to find answers to questions that have haunted her family for decades.

Suzanne Goldsmith

Suzanne Goldsmith

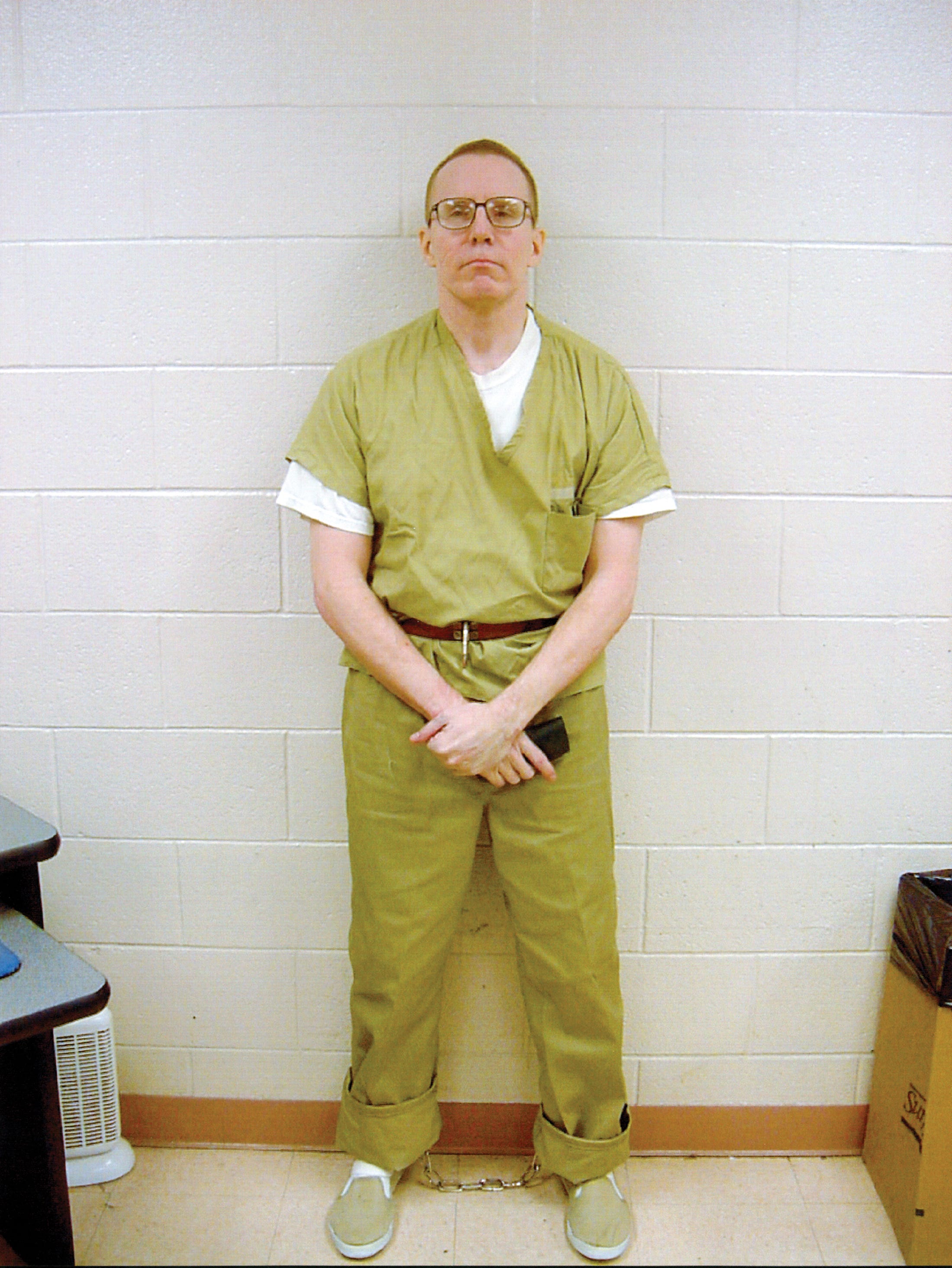

Jennifer Harp-Yanka didn’t say anything to her father before writing her first letter to Michael Swango. She knew a correspondence with the serial killer would worry her dad, a retired police detective, even though it was clear that Swango was never getting out of prison. He was—and still is—locked up in Florence, Colorado, in the nation’s only supermax federal penitentiary, where dangerous killers convicted of unspeakable crimes are kept in solitary confinement under an extraordinary level of security. Others incarcerated there include the Unabomber, the Boston Marathon bomber and El Chapo.

Dear Mr. Swango,

I hope this letter finds you well and I also hope you don’t mind me writing to you. … Believe it or not, your name entered my life around 1984 when I was a young elementary-aged girl. My dad, Richard (Dick) Harp, was a detective and lead investigator for Ohio State University police department and was assigned to your case. After he was assigned, your name came up all the time in my childhood years. Even after my dad had completed his case with you, he and I spent a lot of time wondering how things were going for you.

For Dick Harp, Swango was the one that got away—a vexing case in which he’d felt thwarted in his investigation and blocked from bringing charges against a man he felt sure was a killer (a belief that was later proven true). For Harp-Yanka, now a licensed counselor and a college psychology professor, Swango’s killing career—and her father’s lingering frustration over the case—ignited a drive to understand.

Find more local stories:Subscribe to Columbus Monthly's weekly newsletter, Top Reads

Harp-Yanka began with innocuous questions. She wanted to establish a rapport with Swango. “My first curiosity is just how are things going for you in Florence?” she wrote. She sent the letter off in February 2019. She didn’t think he’d write back.

But in April, a plain white envelope arrived from Colorado. That’s when she called her dad. “I absolutely freaked out,” Harp-Yanka remembers. “I started screaming.” Swango’s letter was printed in pencil with emphatic handwriting on lined paper. It was filled with underlinings, arrows, exclamation points, smiley-face drawings and, oddly, praise for her father.

Dear Jennifer,

First of all, thank you for your most intriguing and unexpected letter. … Please give my best to your father, Richard. I trust he is in good health and will remain so for many more years. I of course remember him and his involvement. I appreciate what he said about me, and let me return the compliment by saying this: He was always extremely professional and polite, far more so, I might add, than some of the state, federal and foreign investigators I have had interactions with.

Then he suggested, tantalizingly, that he had much more to tell her about what had happened during his time in Columbus.

Should we get to know each other better, it might be interesting to explore those things in much greater detail.

He closed his letter with a valediction that suggested such exploration might be possible: “(Hoping to become) your friend, Michael,” he wrote.

If Michael Swango killed as many people as those who investigated him believe, he was astonishingly prolific. According to “Blind Eye,” James B. Stewart’s deeply researched 1999 book about the case, Swango, who has confessed to four killings, very likely murdered 35 people and perhaps 60 or more. He was convicted of injecting victims with poison while working in hospitals in Ohio and New York, and suspected of doing the same elsewhere, including Zimbabwe. He also experimented with poisoning food that he served to colleagues and others. The earliest killing he confessed to, appearing in Franklin County Court of Common Pleas in 2000, was that of Cynthia McGee, a 19-year-old gymnast from Dublin who died while recovering from a car accident at Ohio State University Medical Center in 1984 when Swango was an intern there.

Today, another doctor is under the spotlight in Columbus, accused of killing patients with overdoses of a lethal drug. There may or may not be similarities between the cases of Swango and William Husel, whose trial in that same court was ongoing in late March. But if Husel is found guilty of murder—something that is no longer in doubt in the case of Swango—the outcome will raise the same questions that have puzzled Dick Harp and Jennifer Harp-Yanka for decades. What makes a doctor kill? And how can it be prevented?

Timeline:Michael Swango's Life and Crimes

Michael Swango's early history with poisonings

In October 1984, Dick Harp’s boss, OSU police chief Pete Herdt, asked him to look into Swango’s history at Ohio State Medical Center. The department had received a call from police in Quincy, Illinois, where Swango was under investigation for a series of bizarre, though nonfatal, poisonings at his workplace, a medical transport company. The police wanted to know if anything suspicious had happened when he was a surgical intern at Ohio State earlier in the year.

As Harp and his colleagues began asking questions, they learned that some Ohio State nurses had suspected Swango of foul play. Indeed, the administration and medical staff had investigated him after three witnesses accused him of tampering with an IV just before a patient went into respiratory arrest. (The patient recovered.) There were rumors that Swango might be connected to a rash of unexplained deaths on the neurosurgery ward. But hospital administrators found Swango’s denials more credible than the accounts of the uneasy nurses. They didn’t contact law enforcement. Instead, they gave him a passing grade and recommended him for licensure—even as they rescinded his invitation to stay on for a residency in neurosurgery. In effect, they sent him away to be someone else’s problem.

The Ohio State police were irritated that hospital officials didn’t contact them earlier. They found themselves playing catch-up, frustrated by a lack of documentation of the hospital’s earlier inquiry, as well as reluctance and even opposition from hospital staff. “As we dug in to talk to more and more people, it looked like, ‘We got a serious problem down here, and this guy may have killed people,’” Harp says.

The police’s concerns were later validated when OSU president Edward Jennings asked the law school dean, James Meeks, to look into the university’s handling of Swango. The Meeks report found the medical center’s investigation “far too superficial,” noting that some witnesses were not interviewed, there was no attempt to reconcile differing accounts, there was no central record kept of the investigation, and critical evidence was ignored, including, “most disappointing of all,” according to Meeks, a used syringe a nurse found in a patient’s room immediately after a suspicious death. The syringe was not taken as evidence or tested, and when nobody seemed interested in it, the nurse threw it away.

The police got a warrant and opened up a storage locker Swango rented near campus, where they found and confiscated Vietnam-era ammo belts, scrapbooks filled with articles about fatal accidents and mayhem, and other weird memorabilia. Swango, awaiting trial and still spending time with a girlfriend in Columbus, contacted Harp and asked to see the items the police had taken. They met at the police headquarters, and Swango looked at his things while Harp tried, unsuccessfully, to question him and armed guards watched through one-way glass.

Harp also went to Illinois to see the evidence the Quincy police had uncovered at Swango’s home, which included recipe cards and ingredients for making deadly substances such as ricin. Based on that evidence, the university police exhumed and tested the remains of several Ohio State patients who had died unexpectedly during Swango’s tenure. They didn’t find poison—a substance could have dissipated, and there was no test for ricin—but in one patient, Ricky Delong, who had a tracheotomy, they found gauze lodged in his airway. The coroner reclassified his death as a homicide—a determination the university contested, according to Stewart’s book—but they couldn’t link the gauze to Swango.

Like Harp, Pete Herdt, now retired and living in Washington Court House, continues to blame Ohio State for the failure of his investigation. “If we had received more cooperation from the hospital, I really do feel we could have nailed him for at least one of those murders,” he says. (Ohio State officials declined to comment for this story.)

But the university police didn’t have hard evidence. The Quincy police did: a pitcher of iced tea tainted with ant poison. Swango was convicted in the nonfatal poisonings and received a five-year sentence. He got out in about two and resumed his medical career, using charm, lies and forged documents to get hired. Whenever he came under suspicion, Swango moved on, leaving a trail of unexplained poisoning deaths in his wake at hospitals in North Dakota, New York and Zimbabwe. Swango would not be brought to justice until 2000.

The case hung like a shadow over Harp, and his daughter saw this. While her father focused on the ways he’d been thwarted in his investigation, Harp-Yanka came to focus on what made Swango a killer. She studied psychology in college and became a social worker, then a licensed counselor. She now teaches psychology at New Jersey’s Rowan College in Burlington County, near Philadelphia. She has worked with court-involved patients and those with trauma and substance abuse disorders, as well as children with antisocial tendencies. Once, a 6-year-old stabbed her in the stomach with a sharp pencil hard enough to break the skin, explaining, “Ms. Yanka should have given me a better pencil, or this wouldn’t have had to happen.”

She wondered if a child like that could become a Michael Swango. Could a professional like her stop it from happening?

What made Michael Swango kill?

In his first letter, Swango dangled a hint about his personal development that Harp-Yanka would pursue in subsequent letters.

I am so glad that psychology is your chosen field, and I would love to get into great detail on various topics as time goes on. I should “warn” you, however, [smiley-face], that I am very upfront and candid and will, freely and in intimate detail talk about subjects and taboos that many find uncomfortable. … Please feel free to ask anything you wish about anything that has happened in the past or present. … As a clinical therapist, you must deal with relationship issues all the time. My entire life, starting with a relationship with an older woman in my teens, I have been utterly and completely fascinated by interpersonal relationships and how they define and transform and sometimes destroy lives.

The relationship with an older woman intrigued Harp-Yanka. Neither her religion nor her psychological training allowed her to believe a person could be entirely evil, although some might have a genetic propensity to sociopathy. Through her experiences with clients, she had concluded that sometimes a life event could serve as a “tipping point” that caused them to move from unspeakable thoughts to unspeakable acts. If there was a sexual component to Swango’s impulse to kill—although this is unknown—perhaps this relationship was a key.

In her next letter to Swango, she described her work with a patient who had been damaged by an early, violent sexual relationship with an older woman. “I bring this up because I’m very curious when this relationship happened to you,” she wrote. “I’d love to explore your experiences to see how this relationship you mentioned really affected your own trajectory.”

In several of his ensuing letters, Swango dangled tantalizing references to the relationship without ever sharing any details. Just part of the “mind games” she expected of someone with his psychological profile, Harp-Yanka reflects. In an October 2019 letter, Swango wrote:

I am certainly open to sharing with you details about that relationship. Remarkable that you explored a somewhat similar situation in detail with the patient you mentioned. ... I certainly have my own ideas and conclusions about how that relationship (longer and more complex than you might imagine) affected my later life, especially future intimate relationships, but your thoughts and conjectures would be most welcome. I should tell you that human interpersonal relationships have always been utterly fascinating to me.

Over three years, Harp-Yanka and Swango wrote back and forth, exchanging a dozen or more letters. Sometimes, Harp-Yanka says, Swango seemed to be trying to shock her—as when he recommended she watch a documentary series about the cult leader Jim Jones and the mass suicide he led at Jonestown. “He wanted to see if I would be like, ‘Why is Michael Swango watching Jim Jones? That’s really crazy and weird.’ But I didn’t bite. I just wrote back and said that I watched it.”

While Swango avoided any flat-out confessions in his letters, he often touched on—even boasted about—aspects of his criminal career.

I’ve actually been able to assist several students over the years who have written and [asked] for help on a particular project. There was a woman … who wrote a graduate thesis on medical malpractice and malfeasance, and we actually talked quite a bit about Ohio State, and a student in the forensic science program at Duquesne University who was taking a forensic toxicology course and needed some information on less well-known (the press always called them “exotic”) toxins. It was actually quite amusing—his instructor asked him, “Where the hell did you hear about that?!”

In her letters, Harp-Yanka talked about her house, her garden, her pets. She described her world under COVID. She passed along questions from her students. The letters appear casual, conversational—but she says they were exhausting to write. “Sometimes it takes me days, even a week to figure out how I want to talk to him and respond, because I want him to talk,” she says. “People with his type of disorder, if you upset them, they shut you off and you’re done.”

In the summer of 2020, she mentioned a new development: She and her father were to travel to New York, along with Herdt, to be interviewed by CNN for a documentary about Swango. The two retired cops had high hopes that the show would finally tell the story of their thwarted investigation.

But they would find the CNN documentary disappointing. They were surprised to learn the final product would be part of a schlocky true-crime series on HLN, a CNN subsidiary: Very Scary People, hosted by Donnie Wahlberg.

When she learned the title of the show, Harp-Yanka wrote a letter to Swango that more earnestly than in any of her earlier letters described her desire to know why he killed—a desire linked to her faith in the basic goodness of humans.

Michael, you may have a complicated, long criminal past, but just in the last year or so that we’ve exchanged letters, you are way more than someone to be pigeonholed as a “Very Scary” person. Would you agree?

I think what got me thinking of all of these things is because anyone I talked to about you, especially my students, and of course during the CNN interview, [asks] me as the mental health professional is, why? Why did you go down the path that you did? What happened? … Here is my question for you, Michael, if it’s OK for me to ask: What needed to be different for you to have taken a different path? What is it that you might have needed to take a different turn?

I hope you don’t think I’m getting kooky when I say this, but I wish you could see me right now. I’m starting to tear up as I type out those questions to you. I think it’s because I’m sad that someone couldn’t have helped you change your path.

Swango never answered her question.

'A perfect storm'

The correspondence continues, but more time elapses between letters. Three years after her first letter to Swango, Harp-Yanka no longer believes that he will reveal to her the key to his psychopathology. But she says her clinical self is at peace with her conclusion that a “perfect storm” of factors, some of which she’s read about and some of which emerged in his letters, created the human that was capable of tipping into murderousness. High intelligence. Parenting that was both authoritarian and emotionally neglectful. A failure to rebel. Perhaps there was a genetic component as well, she says. “What we’ve learned is that if a child truly doesn’t express empathy early on, there are early interventions that can be done from a therapeutic standpoint to help teach your child empathy.” Maybe that is something to explore in her practice, and with students.

Harder to accept is that Swango will never confess to the full breadth of what he did. Intellectually, she knew from the start that her correspondence with Swango was unlikely to extract any confessions. She never claimed that as a goal. But for her father’s sake—and for the sake of the many families who still don’t know if their loved one was murdered—part of her was hoping it would.

“The emotional side of it, for me, the family side, will probably never be resolved because he’ll never admit to what-all he really did. And that’s very frustrating and sad. It makes me sad for my dad.”

But she also says the experience of sharing Swango’s letters and revisiting the past has brought her closer to her father. Sitting with her parents at their dining room table in Pickerington in late January, Harp-Yanka recalled a moment in the green room before their interviews with CNN in New York. She was watching her father and Herdt catch up; the two hadn’t seen each other in years. Then the mood in the room changed. “And I realize I’m looking at, and I say this with love, a couple of old cops, and they’re talking about Swango, and all of a sudden you could see it in their face and you could hear it in their voice: They’re sad. Frustrated. Disappointed that this had never been solved and at what they had been up against. You could see how much it had affected the two of them. I saw it in their faces.”

Dick Harp was touched by her memory of that day. “She felt sad that we had worn ourselves out trying to get this guy, without success,” he says, some weeks later. “That came unexpected to me. It was heartwarming, for lack of a better word. Because, you know, we all have to do what we have to do. And here we are.”

This story is from the April 2022 issue of Columbus Monthly.